|

AMY

JOHNSON

AUTOMOTIVE

A TO Z CLIMATE CHANGE FUEL

CELLS HYDROGEN

LANDING PAGE SPEEDACES

A- Z UTILITIES

Amy

Johnson, aviator, engineer and speed ace

During

what many see as the golden age of aviation, one young woman, at the age 27,

entered an almost exclusively male dominated way of life.

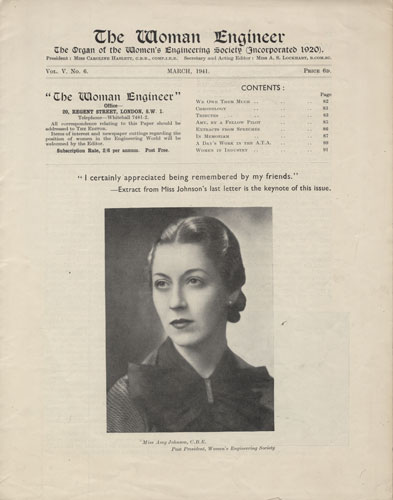

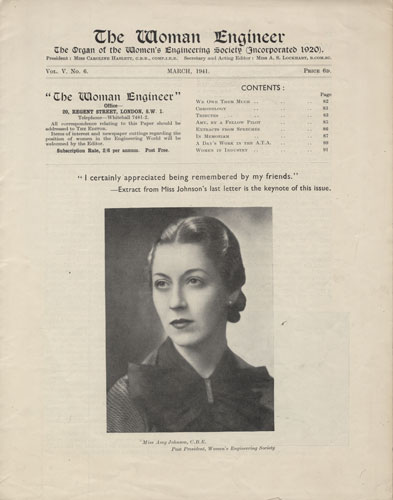

Amy Johnson CBE (1 July 1903 – 5 January 1941), the famous English aviator, was the first

female pilot to fly solo from Britain to Australia. Either solo or together with her husband, Jim Mollison, she set many long-distance flying records in the 1930s. She died tragically young, before reaching the age of 40, when the Airspeed Oxford she was flying for the Air Transport Auxiliary (ATA), reportedly ran out of fuel, and crashed into the Thames Estuary. Although Amy had bailed out her body was never

found. More of that tragedy later.

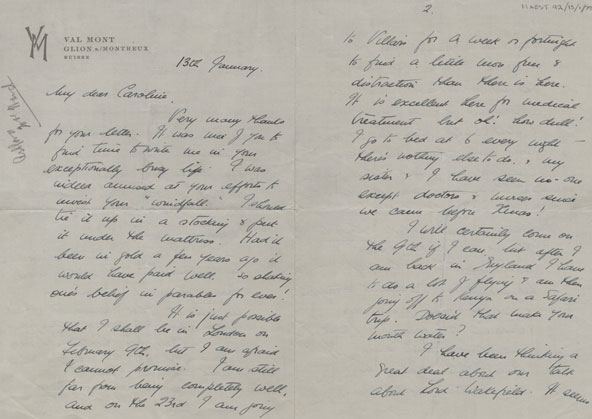

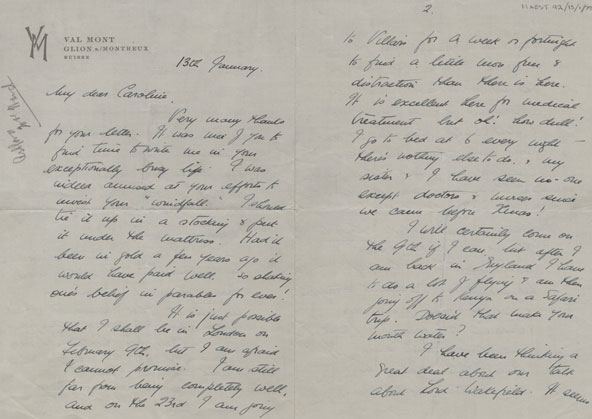

Amy Johnson was a 2-term President of the Women’s Engineering Society (WES), for the years 1935/36 and 1936/37, and had been a member of WES before that. Before and during the years of her Presidency she corresponded frequently with the Honorary Secretary of WES at that time, Caroline

Haslett, some of which letters survive.

FUNDING

Johnson obtained the funds for her first aircraft from her father, who would always be one of her strongest supporters, and Lord Wakefield. She purchased a secondhand de Havilland DH.60 Gipsy Moth G-AAAH and named it Jason after her father's business trade mark.

Johnson achieved worldwide recognition when, in 1930, she became the first woman to fly solo from England to Australia. Flying G-AAAH Jason, she left Croydon Airport, Surrey, on 5 May and landed at Darwin, Northern Territory on 24 May 11,000 miles (18,000 km). Six days later she damaged her aircraft while landing downwind at Brisbane airport and flew to Sydney with Captain Frank Follett while her plane was repaired. Jason was later flown to Mascot, Sydney, by Captain Lester Brain.

She received the Harmon Trophy as well as a CBE in George V's 1930 Birthday Honours in recognition of this achievement, and was also honoured with the No. 1 civil pilot's licence under Australia's 1921

Air Navigation Regulations.

Johnson next obtained a de Havilland DH.80 Puss Moth G-AAZV which she named Jason II. In July 1931, she and co-pilot Jack Humphreys became the first people to fly from London to Moscow in one day, completing the 1,760 miles (2,830 km) journey in approximately 21 hours. From there, they continued across Siberia and on to Tokyo, setting a record time for Britain to Japan.

In 1932, Johnson married Scottish pilot Jim Mollison, who had proposed to her during a flight together some eight hours after they had first met. In July 1932, Johnson set a solo record for the flight from London to Cape Town, South Africa in Puss Moth G-ACAB, named Desert Cloud, breaking her new husband's

record, potentially sealing the dissolution of the marriage 6 years later.

In July 1933, Johnson together with Mollison flew the G-ACCV, named "Seafarer," a de Havilland DH.84 Dragon I nonstop from

Pendine Sands, South Wales, heading to Floyd Bennett Field in Brooklyn, New York. The aim was to take “Seafarer” to the starting point for the Mollison's attempt at achieving a world record distance flying non-stop from New York to Baghdad.

Running low on fuel and now flying in the dark of night, the pair made the decision to land short of New York. Spotting the lights of Bridgeport Municipal Airport (now Sikorsky Memorial Airport) in Stratford, Connecticut they circled it five times before crash landing some distance outside the field in a drainage ditch. Both were thrown from the aircraft but suffered only cuts and gashes. After recuperating, the pair were feted by New York society and received a ticker tape parade down Wall Street.

The Mollisons also flew, in record time, from Britain to India in 1934 in G-ACSP, named "Black Magic", a de Havilland DH.88 Comet as part of the Britain to Australia MacRobertson Air Race, but were forced to retire from the race at Allahabad because of engine trouble.

In September 1934, Johnson (under her married name of Mollison) became the youngest President of the Women's Engineering Society, having been vice-president since 1934. She was active in the society until her death.

In May 1936, Johnson made her last record-breaking flight, regaining her Britain to South Africa record in G-ADZO, a Percival Gull Six. The same year she was awarded the Gold Medal of the Royal Aero Club.

In 1938, Johnson overturned her glider when landing after a display at Walsall Aerodrome in England, but was not seriously hurt. The same year, she divorced Mollison. Soon afterwards, she reverted to her maiden name.

TRAGIC DEATH

Writing a last letter to her friend Caroline Haslett, on New Years Day 1941, "I hope the gods will watch over you this year, and I wish you the best of luck (the only useful thing not yet taxed!)." On 5 January 1941, while flying an Airspeed Oxford for the ATA from Prestwick via RAF Squires Gate to RAF Kidlington near Oxford, Johnson went off course in adverse weather conditions. Reportedly out of fuel, she bailed out as her aircraft crashed into the

Thames Estuary near Herne Bay.

When her plane ran critically short of fuel she spotted the Royal Navy convoy in the Thames and bailed out, for the first and last time in her glittering career, hoping to be rescued.

Seconds after opening her parachute she crashed into the water. Her fingers turned white as she waved frantically for help, before she vanished.

It was presumed she had drowned but fresh evidence may finally explain why her body was never found. It is claimed she was accidentally killed by her rescue ship.

The revelation comes from Harry Gould, 84, whose father, also called Harry, was a Naval reservist on HMS Haslemere.

Harry says the ship had hit a sandbank and was put in reverse to break free.

He says: “So many of the crew were trying to help Amy, but with the ship moving they couldn’t reach her.

“My father saw she was getting too close to the stern and shouted up to the bridge, telling them to cut the engines because they were going the wrong way. But they didn’t listen.

“One of the officers shouted back, ‘Don’t you tell me what to do!’ If they had listened to him Amy might have survived.

“A few seconds later she was dragged under the boat. Everyone thought she had been cut to pieces by the propellers. It’s an awful way for such a special person to die.” Harry and his crewmates were not called to give evidence at the 1943 inquiry into Amy’s death.

But hidden in the official report there is support for his story, from RAF clerk Derek Roberts, whose friend Cpl Bill Hall was also on HMS Haslemere.

It reveals how Amy drifted near the ship, identified herself and complained the water was “bitterly cold”, urging the crew to “get her out as soon as possible”.

“They threw her a rope but she couldn’t get hold if it. Then someone dashed up to the bridge and reversed the ship’s engines. As a result, she was drawn into the propeller and chopped to pieces.” The ship’s captain Lt Cdr Walter Fletcher dived into the

water, with a rope tied around his waist, to search for her.

He had to be pulled from the river and died of hypothermia later that day. He was awarded the Albert Medal for his courage.

Dr Gill says a sailor “was within five feet of reaching Amy’s hand. They must have looked into each other’s eyes. It’s tragic.

“This ship should have gone down in history as the ship that saved Amy’s life. Instead, historians are beginning to conclude that the propellers of the Haslemere killed her and that’s why her body was never found. That wasn’t even mentioned when her parents were still alive.”

“This is still speculation as without a body there is no evidence. But it seems possible the Royal Navy would cover up what happened as they didn’t want to admit they had killed the most popular female pilot in the world.”

Other more fanciful theories include a claim she was shot down by friendly fire after failing to give British gunners the correct radio code and that she was flying to France with a German spy she had fallen in love with.

Remarkably Mr Gould, who saw Amy crash, had lived and worked in the Hessle Lane fishing community in Hull where Amy was raised in a family of fish merchants.

But unlike Mr Gould, Amy was so embarrassed by her northern roots she ditched her Yorkshire accent when she became famous.

Setting

a style that is popular in 2020, Amy appreciated the value of warm clothing,

but still managed to look like a model.

AMY IN POPULAR CULTURE

Johnson's life has been the subject of a number of treatments in film and television, some more accurately biographical than others. In 1942, a film of Johnson's life, They Flew Alone, was made by director-producer Herbert Wilcox, starring Anna Neagle as Johnson, and Robert Newton as Mollison. The movie is known in the United States as Wings and the Woman. Amy! (1980) was an avant-garde documentary written and directed by feminist film theorist Laura Mulvey and semiologist Peter Wollen. In the 1991 Australian television miniseries The Great Air Race, aka Half a World Away, based on the 1934 MacRobertson Air Race, Johnson was portrayed by Caroline Goodall.

Johnson earned a passing mention in other works such as the 2007 British film adaption of Noel Streatfeild's 1936 novel Ballet Shoes, wherein the character Petrova is inspired by Johnson in her dreams of becoming an aviator.

In radio, the 2002 BBC Radio broadcast The Typist who Flew to Australia, a play by Helen Cross, presented the theme that Johnson's aviation career was prompted by years of boredom in an unsatisfying job as a typist and sexual adventures including a seven-year affair with a Swiss businessman who married someone else.

In music, Johnson inspired a number of works, including the song "Flying Sorcery" from Scottish singer-songwriter Al Stewart's album, Year of the Cat (1976). A Lone Girl Flier and Just Plain Johnnie (Jack O'Hagan) sung by Bob Molyneux, and Johnnie, Our Aeroplane Girl sung by Jack

Lumsdaine. Queen of the Air (2008) by Peter Aveyard is a musical tribute to Johnson.

More fictionalised portrayals include a Doctor Who Magazine comic story in 2013 entitled "A Wing and a Prayer", in which the time-travelling Doctor encounters Johnson in 1930. He tells Clara Oswald her death is a fixed point in time. Clara realises what's important is that it appears Amy died. They save her from drowning then took her to the planet Cornucopia. The character Worrals in the series of books by Captain W.E. Johns was modelled on Amy Johnson.

After

the Wright

Brothers conquest of the air at Kitty

Hawk in 1903, the next major air conquest was from Calais to Dover across the English

Channel. The successful pilot was Louis Bleriot

on the 25th of July 1909. The

next big Pond was the Atlantic

Ocean with Charles

Lindbergh in 1927.

Then in

1928 Sir

Charles Kingsford Smith crossed the Pacific

Ocean from Mana to Brisbane, also completing a World Circumnavigation

in 1930. The ladies got a look in with the exceptional achievement of Amy

Johnson in 1930 she managed Croydon, London to Brisbane, Australia solo.

GOING

ELECTRIC 2015

Then

came Hughes

Duwal on the 9th of July 2015, in his electrically propelled Colomban E-Cristaline,

pipping Airbus to the post with their E-Fan on the 10th of July 2015.

LINKS

& REFERENCE

http://www.solarnavigator.net/aviation_and_space_travel/charles_lindbergh.htm

http://elizabethqueenseaswann.com/Events_Records_Attempts_Solar_Powered/Cross_Channel

http://www.elizabethqueenseaswann.com/Transatlantic/TransAtlantic_Solar_Powered_Autonomous_Records_Attempt.html

Louis

Bleriot in the early hours of the 25th July 1909, making provision for taking

off before the other pilots had a chance to snatch victory from him.

Copyright

© website 2020, all rights reserved, save for educational and media

review purposes. You do not need permission to use our information if it

is to help promote a low carbon economy. This is a low carbon website that

loads quickly and is as kept simple as possible while still providing

useful information. Cleaner

Ocean Foundation Ltd and Climate

Change Trust.

|