|

SEWING MACHINES - A SHORT HISTORY

|

||

|

A sewing machine is a mechanical (or electromechanical) device that joins fabric using thread. Sewing machines make a stitch, called a sewing-machine stitch, usually using two threads although machines exist that stitch using one, three, four or more threads. As a lad these wonderful machines interested me. Later, I collected a few, simply because some of the oldies are so beautiful.

Sewing machines can make a great variety of plain or patterned stitches. They include means for gripping, supporting, and conveying the fabric past the sewing needle to form the stitch pattern. Most home sewing machines, as with many industrial machines, use a two thread stitch called the lockstitch. Some older machine types are chain stitch machines and sergers.

The fabric shifting mechanism may be a simple workguide or may be pattern-controlled (e.g., jacquard type). Some machines can create embroidery-type stitches. Some have a work holder frame. Some have a workfeeder that can move along a curved path, while others have a workfeeder with a work clamp.

History of the sewing machine

Before the invention of a usable machine for sewing or dress design, everything was sewn by hand. Most early attempts tried to replicate this hand sewing method and were generally a failure. Some looked to embroidery, where the needle was used to produce decorative, not joining stitches. This needle was altered to create a fine steel hook – called an agulha in Portugal and aguja in Spain. This was called a crochet in France and could be used to create a form of chain stitch. This was possible because when the needle was pushed partly through fabric and withdrawn, it left a loop of thread. The following stitch would pass through this first loop whilst creating a loop of its own for the next stitch, this resembled a chain – hence the name.

The first known attempt at a mechanical device for sewing was by the German born Charles Fredrick Wiesenthal, who was working in England. He was awarded British Patent No. 701 in 1755 for a double pointed needle with an eye at one end. This needle was designed to be passed through the cloth by a pair of mechanical fingers and grasped on the other side by a second pair. This method of recreating the hand sewing method suffered from the problem of the needle going right through the fabric, meaning the full length of the thread had to do so as well. The mechanical limitations meant that the thread had to be kept short, needing frequent stops to renew the supply.

In 1790 British Patent No. 1764 was awarded to Thomas Saint, a cabinetmaker of London. Due to several other patents dealing with leather and products to treat leather, the patent was filed under "Glues & Varnishes" and was not discovered until 1873 by Mr. Newton Wilson. Wilson built a replica to the patent's specifications and it had to be heavily modified before the machine would stitch – suggesting that Saint never actually made a machine of his own. Saint's design had the overhead arm for the needle and a form of tensioning system, which was to become a common feature of later machines.

There were various attempts and patents awarded for chain stitch machines of varying types from 1795-1830, none of which were used to any degree of success – many of which didn't work correctly at all. A French tailor Barthelemy Thimonnier made the next major breakthrough. He did not try to replicate the human hand stitch, looking instead for a way of finding a stitch, which could be made quickly and easily by machine. His machine worked by using a horizontal arm mounted on a vertical reciprocating bar, the needle-bar projected from the end of the horizontal arm.

The cloth was supported on a hollow, horizontal fixed arm, with a hole on the topside, which the needle projected through at the lowest part of its stroke. Inside the arm was a hook, which partly rotated at each stroke in order to wrap the thread (fed from the bobbin onto the hook) around the needle at each stroke. The needle then carried the thread back through the cloth with the upward motion of its stroke. This formed the chain stitch, which held the cloth together.

The machine was powered by means of a foot pedal. The easiest way to describe this is to picture the machine working upside-down from how sewing machines are generally thought of today – the stitch was formed on the top of the cloth, not the bottom as with most other chain stitch machine made since. Thimonnier was awarded a French patent in 1830 and 80 of these machines were installed in a factory in Paris to stitch Soldiers clothing. Other tailors concerned for their livelihood invaded the factory and smashed the machines.

Chain stitch has one major drawback – it is very weak, the stitch can easily be pulled apart. A stitch more suited to machine production was needed, it was found in the lock stitch. A lock stitch is created by two separate threads interlocking through the two layers of fabric, resulting in a stitch, which looks the same from both sides of the fabric. Although the credit for the lock stitch machine is generally given to Elias Howe, Walter Hunt first developed it over ten years before in 1834. His machine used an eye-pointed needle (with the eye and the point on the same end) carrying the upper thread, and a shuttle carrying the lower thread. The curved needle moved through the fabric horizontally, leaving the loop as it withdrew. The shuttle passed through the loop, interlocking the thread. The feed let the machine down – requiring the machine to be stopped frequently to set up again. Hunt grew bored with his machine and sold it without bothering to patent it.

Singer sewing machine

Elias Howe patented his machine in 1846; using a similar method to Hunt's, except the fabric was held vertically. The major improvement he made was to put a groove in the needle running away from the point, starting from the eye. After a lengthy stint in England trying to attract interest for his machine he returned to America to find various people infringing his patent. He eventually won his case in 1854 and was awarded the right to claim royalties from the manufacturers using ideas covered in his patent. Isaac Merritt Singer has become synonymous with the sewing machine. Trained as an engineer, he saw a rotary sewing machine being repaired in a Boston shop. He thought it to be clumsy and promptly set out to design a better one. His machine used a flying shuttle instead of a rotary one; the needle was mounted vertically and included a presser foot to hold the cloth in place. It had a fixed arm to hold the needle and included a basic tensioning system.

This machine combined elements of Thimonnier’s, Hunts and Howe’s machines. He was granted an American Patent in 1851 and it was suggested he patent the foot pedal (or Treadle) used to power some of his machines, however it had been in use for too long for a patent to be issued. When Howe learned of Singer’s machine he took him to court. Howe won and Singer was forced to pay a lump sum for all machines already produced. Singer then took out a license under Howe’s patent and paid him $15 per machine. Singer then entered a joint partnership with a lawyer named Edward Clark, and they formed the first hire purchase scheme to allow people to afford their machines.

Meanwhile Mr. Allen Wilson had developed a reciprocating shuttle, which was an improvement over Singer’s and Howe’s. However, John Bradshaw had patented a similar device and was threatening to sue. Wilson decided to change track and try a new method. He went into partnership with Nathaniel Wheeler to produce a machine with a rotary hook instead of a shuttle. This was far quieter and smoother than the other methods and the Wheeler and Wilson Company produced more machines in 1850s and 1860s than any other manufacturer. Wilson also invented the four-motion feed mechanism; this is still seen on every machine today. This had a forward, down, back, and up motion, which drew the cloth through in an even and smooth motion.

Through the 1850s more and more companies were being formed and were trying to sue each other. Charles Miller patented the first machine to stitch buttonholes (US10609). In 1856 the Sewing Machine Combination was formed, consisting of Singer, Howe, Wheeler and Wilson, and Grover and Baker. These four companies pooled their patents, meaning that all the other manufacturers had to obtain a license and pay $15 per machine. This lasted until 1877 when the last patent expired.

James Edward Allen Gibbs (1829-19502), a farmer from Raphine in Rockbridge County, Virginia who patented the first chain-stitch single-thread sewing machine on June 2, 1857. In partnership with James Wilcox, Gibbs became a principal in Wilcox & Gibbs Sewing Machine Company. Wilcox & Gibbs commercial sewing machines are still made and used in the 21st century.

Sewing machines continued being made to roughly the same design, with more lavish decoration appearing until well into the 1900s when the first electric machines started to appear. At first these were standard machines with a motor strapped on the side. As more homes gained power, these became more popular and the motor was gradually introduced into the casing.

Modern machines are computer controlled and use stepper motors or sequential cams to achieve very complex patterns. Most of these are now made in Asia and the market is becoming more specialized, as fewer families own a sewing machine.

Needle plate, foot and transporter of a sewing machine

Without the sewing machine, the world would be a very different place. Like the automobile, the cotton gin and countless other innovations from the past 300 years, the sewing machine takes something time-consuming and laborious and makes it fast and easy. With the invention of the mechanized sewing machine, manufacturers could suddenly produce piles of high-quality clothing at minimal expense. Because of this technology, the vast majority of people in the world can now afford the sort of sturdy, finely-stitched clothes that were a luxury only 200 years ago.

In this article, we'll take look at the remarkable machine that makes all of this possible. As it turns out, the automated stitching mechanism at the heart of a sewing machine is incredibly simple, though the machinery that drives it is fairly elaborate, relying on an assembly of gears, pulleys and motors to function properly. When you get down to it, the sewing machine is among the most elegant and ingenious tools ever created.

Sewing machines are something like cars: There are hundreds of models on the market, and they vary considerably in price and performance. At the low-end of the scale, there are conventional no-frills electric designs, ideal for occasional home use; at the high-end, there are sophisticated electronic machines that hook up to a computer. Textile companies have many machines to choose from, including streamlined models specifically designed to sew one particular product.

But just like cars, most sewing machines are built around one basic idea. Where the heart of a car is the internal combustion engine, the heart of a sewing machine is the loop stitching system.

The loop stitch approach is very different from ordinary hand-sewing. In the simplest hand stitch, a length of thread is tied to a small eye at the end of a needle. The sewer passes the needle and the attached thread all the way through two pieces of fabric, from one side to the other and back again. In this way, the needle runs the thread in and out of the fabric pieces, binding them together.

While this is easy enough to do by hand, it is extremely difficult to pull off with a machine. The machine would have to release the needle on one side of the fabric just as it grabbed it again on the other side. Then it would have to pull the entire length of loose thread through the fabric, turn the needle around and do the whole thing in reverse. This process is way too complicated and unwieldy for a simple machine, and even by hand it only works well with short lengths of thread.

Instead, sewing machines pass the needle only part-way through the fabric. On a machine needle, the eye is right behind the sharp point, rather than at the end.

The needle is fastened to the needle bar, which is driven up and down by the motor via a series of gears and cams (more on this later).

When the point passes through the fabric, it pulls a small loop of thread from one side to the other. A mechanism underneath the fabric grabs this loop and wraps it around either another piece of thread or another loop in the same piece of thread. In the next couple of sections, we'll see exactly how this system works.

Lock and Chain

The simplest loop stitch is the chain stitch. To sew a chain stitch, the sewing machine loops a single length of thread back on itself. You can see how one version of this stitch works in the diagram below.

The fabric, sitting on a metal plate underneath the needle, is held down by a presser foot. At the beginning of each stitch, the needle pulls a loop of thread through the fabric. A looper mechanism, which moves in synch with the needle, grabs the loop of thread before the needle pulls up. Once the needle has pulled out of the fabric, the feed dog mechanism (which we'll examine later) pulls the fabric forward.

When the needle pushes through the fabric again, the new loop of thread passes directly through the middle of the earlier loop. The looper grabs the thread again and loops it around the next thread loop. In this way, every loop of thread holds the next loop in place.

The main advantage of the chain stitch is that it can be sewn very quickly. It is not especially sturdy, however, since the entire seam can come undone if one end of the thread is loosened. Most sewing machines use a sturdier stitch known as the lock-stitch. You can see how the typical lock-stitch mechanism works in the animation below.

The most important element of a lock-stitch mechanism is the shuttle hook and bobbin assembly. The bobbin is just a spool of thread positioned underneath the fabric. It sits in the middle of a shuttle, which is rotated by the machine's motor in synch with the motion of the needle.

Just as in a chain-stitch machine, the needle pulls a loop of thread through the fabric, rises again as the feed dogs move the fabric along, and then pushes another loop in. But instead of joining the different loops together, the stitching mechanism joins them to another length of thread that unspools from the bobbin.

When the needle pushes a loop through the thread, the rotary shuttle grips the loop with a hook. As the shuttle rotates, it pulls the loop around the thread coming from the bobbin. This makes for a very sturdy stitch.

In the next section, we'll see how the sewing machine moves all of these components in synch.

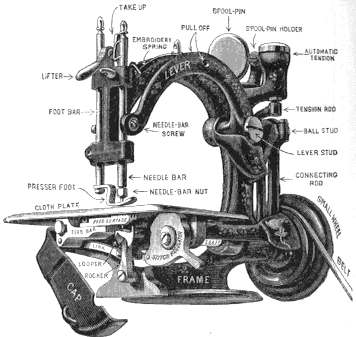

Wilcox & Gibbs sewing machine

The General Assembly

In this diagram, the electric motor is connected to a drive wheel by way of a drive belt. The drive wheel rotates the long upper drive shaft, which is connected to several different mechanical elements. The end of the shaft turns a crank, which pulls the needle bar up and down. The crank also moves the thread-tightening arm. Moving in synch with the needle bar, the tightening arm lowers to create enough slack for a loop to form underneath the fabric, then pulls up to tighten the loop after it is released from the shuttle hook.

The thread runs from a spool on the top of the machine, through the tightening arm and through a tension disc assembly. By turning the disc assembly, the sewer can tighten the thread feeding into the needle. The tension must be tighter when sewing thinner fabric and looser when sewing thicker fabric.

The first element along the shaft is a simple belt that turns a lower drive shaft. The end of the lower drive shaft is connected to a set of bevel gears that rotates the shuttle assembly. Since both are connected to the same drive shaft, the shuttle assembly and the needle assembly always move in unison.

The lower drive shaft also moves linkages that operate the feed dog mechanism. One linkage slides the feed dog forward and backward with each cycle. At the same time, another linkage moves the feed dog up and down. The two linkages are synchronized so that the feed dog presses up against the fabric, shifts it forward, and then moves down to release the fabric. The feed dog then shifts backward before pressing up against the fabric again to repeat the cycle.

The motor is controlled by a foot pedal, which lets the sewer vary the speed easily. The cool thing about this design is that everything is linked together, so when you press on the pedal, the motor speeds all of the processes up at the same rate. The process is always perfectly synchronized, no matter how fast the motor is turning.

The sewing machine shown in the diagram can only produce a straight stitch -- a simple stitch that binds fabric with a straight seam. Most modern machines are a lot more flexible; they can produce a variety of stitches and, in some cases, can make complex designs. In the next section, we'll see how modern machines pull this off.

Computer Crafts

This zig-zag stitch is fairly simple to achieve. All you have to do is move the needle assembly from side to side at the same time that it is moving up and down. In a conventional electric machine, the needle bar is attached to an additional linkage, which is moved by a cam on the main drive shaft. When the linkage is engaged, the rotating cam shifts the linkage from side to side. The linkage tilts the needle bar back and forth horizontally in synch with the up and down motion.

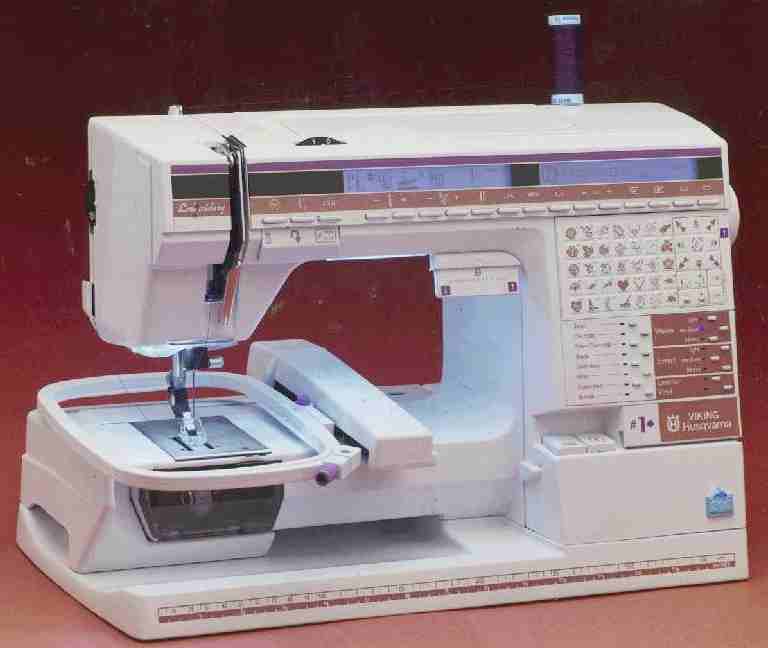

Things work a little differently in the modern machine. Today's high-end home sewing machines have built-in computers, as well as small monitor displays for easier operation. In these models, the computer directly controls several different motors, which precisely move the needle bar, the tensioning discs, the feed dog and other elements in the machine. With this fine control, it is possible to produce hundreds of different stitches. The computer drives the motors at just the right speed to move the needle bar up and down and from side to side in a particular stitch pattern. Typically, the computer programs for different stitches are stored in removable memory disks or cartridges. The sewing-machine computer may also hook up to a PC in order to download patterns directly from the Internet.

Some electronic sewing machines also have the ability to create complex embroidery patterns. These machines have a motorized work area that holds the fabric in place underneath the needle assembly. They also have a series of sensors that tell the computer how all of the machine components are positioned. By precisely moving the work area forward, backward and side to side while adjusting the needle assembly to vary the stitching style, the computer can produce an infinite number of elaborate shapes and lines. The sewer simply loads a pattern from memory or creates an original one, and the computer does almost everything else. The computer prompts the sewer to replace the thread or make any other adjustments when necessary.

Obviously, this sort of high-tech sewing machine is a lot more complex than the fully manual sewing machines of 200 years ago, but they are both built around the same simple stitching system: A needle passes a loop of thread through a piece of fabric, where it is wound around another length of thread. This ingenious method was one of those rare, inspired ideas that changed the world forever.

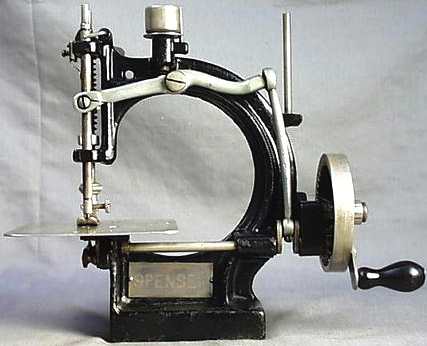

Maxfield Agenoria sewing machine - © Alex Askaroff collection

LINKS and REFERENCEGeneral

Spencer antique sewing machine

Husqvarna Viking sewing machine

Patents and inventors

FIND YOUR PERFECT SWING MACHINE A - Z

No matter what style, design or features you need on your sewing machine, it pays to shop for a good deal ...................

Finding the right sewing machine and service package from numerous high street and online dealers can prove to be an overwhelming challenge. However, there’s more to a search than just finding a cheaper machine. You need to ensure you get a reliable service, sensibly priced spares and reliability.

|

||

|

This website is copyright © 1991- 2024 Electrick Publications. All rights reserved. Max Energy Limited is an educational charity.

|