|

|

|

HOME INDEX CAR MANUFACTURERS BLUEBIRD ELECTRIC ELECTRIC CARS E. CYCLES SOLAR CARS |

|

U.S. Highway 66 or Route 66 was a highway in the U.S. Highway system. One of the original federal routes, US 66 was established on November 11, 1926, though signs did not go up until the following year. It originally ran from Chicago, Illinois through Missouri, Kansas, Oklahoma, Texas, New Mexico, Arizona and California before ending at the beach at Santa Monica for a total distance of 2,448 miles (3,940 km).

Route 66 was a major migratory path west, especially during the dust bowl, and supported the economies of the communities on which the road passed. People became prosperous due to the growing popularity of the highway, and those same people later fought to keep the highway alive even with the growing threat of the new Interstate Highway System.

US 66 was officially decommissioned (that is, officially removed from the US Highway System) in 1985 after it was decided the route was no longer relevant and had been replaced by the Interstate Highway System. The road currently exists as "Historic Route 66", a National Scenic Byway, in the states it once crossed on its journey from Chicago to Santa Monica. It has begun to return to maps in this form.

Route 66 once stretched more than halfway across the United States. For nearly half a century, it was the chief commercial highway and main tourist artery to the West Coast. Over those years, Route 66 gained a certain mythical character that is still fondly remembered. Its days of glory are now faded and most of the old highway has disappeared; yet the nostalgic attraction of this road lives on.

Legislation for public highways in the US first came about in 1916, with revisions in 1921. However, it was not until Congress enacted an even more comprehensive version of the act in 1925 that the government executed its plan for national highway construction.

Officially, the numerical designation 66 was assigned to the Chicago-to-Los Angeles route in the summer of 1926. With that designation came its acknowledgment as one of the nation's principal east-west arteries.

From the outset, public road planners intended U.S. 66 to connect the main streets of rural and urban communities along its course for the most practical of reasons: most small towns had no prior access to a major national thoroughfare.

The West Coast was once severely isolated

Prior to the twentieth century, the West Coast of the United States was severely isolated from the East and Midwest by great barriers of mountains, deserts and barren wastes. Until the transcontinental railroad was completed in 1867, it was quicker and easier to sail a ship around the southern tip of South America than to attempt a journey across our country. At the beginning of the twentieth century, it was still difficult and often perilous to drive from coast to coast. Paved highways frequently ended in the Rocky Mountains or at the edge of the southern deserts. To travel further, often required navigating poorly marked unimproved roads or even dirt tracks. There were few facilities or traveler's amenities along the way.

Route 66 connected Chicago with Los Angeles

Several businessmen from Oklahoma and Illinois decided that the USA needed an intercontinental highway connecting the East Coast with the West Coast. Naturally, they thought it should pass through their hometowns of Springfield Illinois and Oklahoma City. By 1926, they convinced the US government of the strategic value of such a road and construction was finally begun. The road was not fully paved until 1938. They called it Route 66.

Championed by Oklahoman Cyrus Avery in 1923 when the first talks about a national highway system began, US 66 was first signed in 1927 as one of the original U.S. Highways, although it was not completely paved until 1938. Avery was adamant that the highway have a round number and had proposed number 60 to identify it. A controversy erupted over the number 60, largerly from delegates from Kentucky which wanted a Virginia Beach - Los Angeles highway to be US 60 and US 62 between Chicago and Springfield, MO. Arguments and counter-arguments continued and the final conclusion was to have US 60 run between Virginia Beach and Springfield (MO) and the Chicago - Los Angeles route be US 62. Avery settled on "66" (which was unassigned) because he thought the double-digit number would be easy to remember as well as pleasant to say and hear.

After the new federal highway system was officially created, Avery called for the establishment of the U.S. Highway 66 Association to promote the complete paving of the highway from end to end and to promote travel down the highway. In 1927, in Tulsa, Oklahoma, the association was officially established with John T. Woodruff of Springfield, Missouri elected the first president. In 1928, the association made its first attempt at publicity, the "Bunion Derby", a footrace from Los Angeles to New York City, of which the path from Los Angeles to Chicago would be on Route 66. The publicity worked: several dignitaries, including Will Rogers, greeted the runners at certain points on the route. The association went on to serve as a voice for businesses along the highway until it disbanded in 1976.

Route 66 began along the shores of Lake Michigan in Chicago Illinois, that great metropolitan center at the northern extreme of the immense midwestern agricultural basin of the Mississippi River. Chicago was already well connected to the big cities on the East Coast. From there, the road headed south across Illinois, Missouri and the edge of Kansas. In Oklahoma, it turned due west across the panhandle of northern Texas, New Mexico and Arizona before finally entering California. Route 66 ended in Los Angeles at the beaches of Santa Monica.

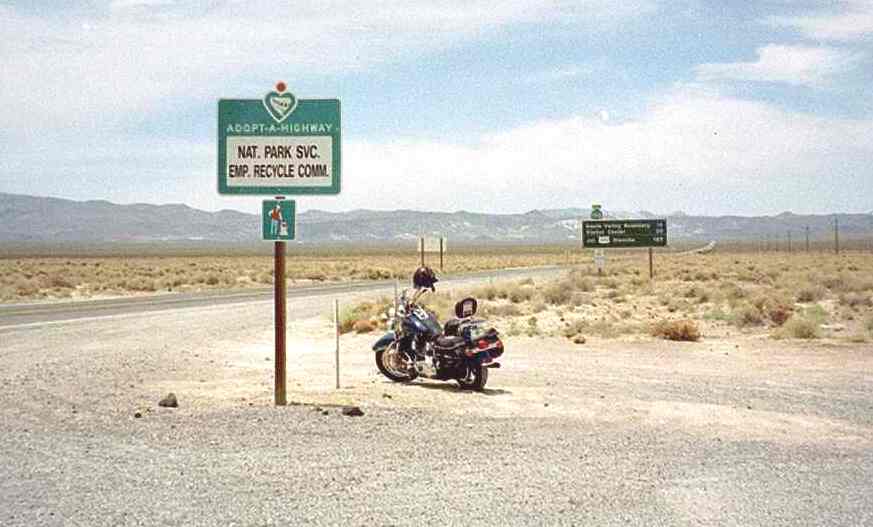

Modern sign in New Mexico along Route 66 - National Scenic Byway

Traffic grew on the highway due to the geography through which it passed. Much of the highway was essentially flat and this made the highway a popular truck route. The Dust Bowl of the 1930s saw many farming families (mainly from Oklahoma, Kansas, and Texas) head west for agricultural jobs in California. Route 66 became the main road of travel for these people, often derogatorily called "Okies". And during the Depression, it gave some relief to communities located on the highway. The route passed through numerous small towns, and with the growing traffic on the highway, helped create the rise of mom-and-pop businesses (mainly as service stations, restaurants, and motor courts) up and down the highway.

The route was nearly 2,400 miles (4,000 km) long. It connected many major cities in the Midwest and the Southwest like Springfield Illinois, St. Louis Missouri, Oklahoma City, Amarillo Texas, Albuquerque New Mexico and Flagstaff Arizona. It also passed through many smaller towns and villages along the way.

It became the favorite East Coast to West Coast highway

Route 66 quickly became the favorite east-west corridor for commercial truck drivers as well as for tourists. It bypassed the high-mountain passes in the Rockies and followed a southern route that was passable all year round.

Much of the early highway, like all the other early highways, was gravel or graded dirt. Due to the efforts of the US Highway 66 Association, Route 66 became the first highway completely paved in 1938. Several places were dangerous, more than one part of the highway became nicknamed "Bloody 66" and gradually work was done to realign these segments to remove dangerous curves. However, one section (through the Black Mountains of Arizona) was fraught with sharp hairpin turns and was the steepest along the entire route--so much so that some early travelers, too frightened at the prospect of driving such a potentially dangerous road, hired locals to negotiate the winding grade. The section remained until 1953--despite this, Route 66 continued to be a popular route.

Area residents along the route soon realized that the incessant stream of motorists required gasoline, food, accommodations and diversions on their journey. Thousands of filling stations, restaurants, cafes, bars, grocery stores, and tourist attractions were erected along the road. Route 66 fostered the popularity of the "motorist hotel" or motel. Roadside attractions included souvenir shops, Indian trading posts, scenic viewpoints, zoos, museums, historical sites and displays of geological phenomena. It was common to see giant Indian tepees, huge cowboy statues and other oddly shaped structures designed to catch the eye of passing motorists along Route 66.

Throughout the 1930s when the great economic depression gripped our country, a drought descended on the Midwestern farming regions. The crops in Oklahoma, Kansas and Missouri died, and the parched earth turned to dust. The Mississippi basin became known as the "dust bowl". Hundreds of thousands of farmers, in economic ruin, lost their homes, loaded their meager possessions on their cars or pickup trucks and headed west in search of employment. They were often called "Oakies" after their home state. Many towns along Route 66 created camping areas or motorist camps where the poor homeless travelers could sleep in their cars for free. Route 66 became the road to the Promised Land of endless sunshine, bountiful harvests and paying jobs in California. American author, John Steinbeck documented this migration in his novel "The Grapes of Wrath" and dubbed route 66 "the mother road".

Bobby Troup wrote "Get your kicks on route 66"

During the Second World War, millions of young men and women traveled across the USA via route 66 as they were sent off to the European or the Pacific battlefields and when they returned home. One such traveler was Bobby Troup, former drummer with the Tommy Dorsey Band and a marine captain. He penned his now famous song "Get your kicks on route 66". In the 1960s, it became the theme song for the immensely popular television series called "Route 66". The mother road was portrayed in many motion pictures and television shows over the years and has earned its place in the history and culture of the USA.

Unfortunately, the mother road fell victim to progress. Superhighways and interstate roads that were bigger, straighter and faster began to replace sections of old route 66 from the mid 1950s onward. By October of 1984, the new interstate highway 40 replaced the last remaining section of route 66 near Williams Arizona. Today, only vestiges of the old mother road remain. You can still find small sections of the old highway all along the original route. The main streets in many small midwestern and southwestern towns are proudly emblazoned with "historic route 66" signs.

The highway fell victim to progress

The longest intact sections of the old road can be found in western Arizona and in eastern California. A100-mile stretch of route 66 curves northwest from Seligman Arizona, through the Havasupai Indian Reservation at Peach Springs, then veers southwest to Kingman Arizona. Ninety miles to the west of Kingman, another 100-mile section of old 66 veers south of I-40 and curves through the Mojave desert through the tiny isolated community of Amboy California before it rejoins the new highway in Ludlow. If you want to sample the character of the old mother road, this is a good location to visit. The towns of Williams, Seligman, Peach Springs and the small city of Kingman have preserved or restored some of the nostalgic roadside attractions. You can still see abandoned tourist accommodations and attractions along the old highway.

If you want to follow the original path of route 66 from Chicago to LA, I suggest you purchase a good route 66 guidebook. Much of its 2400-mile original route is now difficult to find. You will likely find yourself jumping on and off of the newer interstate highways in search of small sections of the old road.

Note: I have been informed that a 110-mile section of original route 66 still exists between Tulsa and Oklahoma City in Oklahoma. The newer Turner Turnpike parallels it but the old mother road still exists.

The longest existing sections of 66 are in Arizona and California

You may want to limit your exploration of route 66 to the stretch between Flagstaff Arizona and Los Angeles. Along that part, you will find the largest remaining sections of the original road with a lot of other scenic attractions in the near vicinity. The Grand Canyon, Sedona, Boulder Dam, Las Vegas, Barstow and the Mojave Desert are all close to old route 66. If you want to do it in style, rent a Corvette or a Harley Davidson motorcycle in Las Vegas, drive down to Kingman, and cruise along the old mother road.

Events

The American Solar Challenge is run along a Route 66 based course. This is a competition to design, build and race solar-powered cars in a cross-country event.

The Formative Years

Route

66 was a highway spawned by the demands of a rapidly changing America.

Contrasted with the Lincoln, the Dixie, and other highways of its day,

route 66 did not follow a traditionally linear course. Its diagonal course

linked hundreds of predominantly rural communities in Illinois, Missouri,

and Kansas to Chicago; thus enabling farmers to transport grain and

produce for redistribution. The diagonal configuration of Route 66 was

particularly significant to the trucking industry, which by 1930 had come

to rival the railroad for preeminence in the American shipping industry.

The abbreviated route between Chicago and the Pacific coast traversed

essentially flat prairie lands and enjoyed a more temperate climate than

northern highways, which made it especially appealing to truckers.

The Depression Years and the War

In his famous social commentary, The Grapes of Wrath, John Steinbeck proclaimed U. S. Highway 66 the "Mother Road." Steinbeck's classic 1939 novel, combined with the 1940 film recreation of the epic odyssey, served to immortalize Route 66 in the American consciousness. An estimated 210,000 people migrated to California to escape the despair of the Dust Bowl. Certainly in the minds of those who endured that particularly painful experience, and in the view of generations of children to whom they recounted their story, Route 66 symbolized the "road to opportunity."

From 1933 to 1938 thousands of unemployed male youths from virtually every state were put to work as laborers on road gangs to pave the final stretches of the road. As a result of this monumental effort, the Chicago-to-Los Angeles highway was reported as "continuously paved" in 1938.

Completion of this all-weather capability on the eve of World War II was particularly significant to the nation's war effort. The experience of a young Army captain, Dwight D. Eisenhower, who found his command bogged down in spring mud near Ft. Riley, Kansas, while on a coast-to-coast maneuver, left an indelible impression. The War Department needed improved highways for rapid mobilization during wartime and to promote national defense during peacetime. At the outset of American involvement in World War II, the War Department singled out the West as ideal for military training bases in part because of its geographic isolation and especially because it offered consistently dry weather for air and field maneuvers.

Route 66 helped to facilitate the single greatest wartime manpower mobilization in the history of the nation. Between 1941 and 1945 the government invested approximately $70 billion in capital projects throughout California, a large portion of which were in the Los Angeles-San Diego area. This enormous capital outlay served to underwrite entirely new industries that created thousands of civilian jobs.

The Postwar Years

The death knell for Route 66 came in 1956 with the signing of the Interstate Highway Act by President Dwight Eisenhower. As a general fighting in the European theater during World War II, Eisenhower was impressed by Germany's high-speed roadways, or "autobahnen." Eisenhower envisioned a similar system of roads for the US in which one could conceivably drive at high speed from one end of the country to the other without stopping as well as making it easier to mobilize troops in the event of a national emergency.

During its nearly 60 year existence, Route 66 was under constant change. As highway engineering became more sophisticated, engineers were constantly looking for more direct routes between cities and towns. Increased traffic led to a number of major and minor realignments of US 66 through the years, particularly in the years immediately following World War II when Illinois began widening US 66 into a four-lane highway through virtually the entire state from Chicago to the Mississippi River just east of St. Louis, MO, and included bypasses around virtually all of the towns. By the early-to-mid 1950s, Missouri also upgraded its sections of US 66 to four lanes complete with bypasses. Most of the newer four-lane 66 paving in both states was upgraded into the interstate highway system in later years.

After the war, Americans were more mobile than ever before. Thousands of soldiers, sailors, and airmen who received military training in California, Arizona, New Mexico, Oklahoma, and Texas abandoned the harsh winters of Chicago, New York City, and Boston for the "barbecue culture" of the Southwest and the West. Again, for many, Route 66 facilitated their relocation.

One such emigrant was Robert William Troup, Jr., of Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, better known as 'Bobby Troup', pianist with the Tommy Dorsey band and an ex-Marine captain. He penned a lyrical road map of the now famous cross-country road in which the words, "get your kicks on Route 66" became a catch phrase for countless motorists who moved back and forth between Chicago and the Pacific Coast. The popular recording was released in 1946 by Nat King Cole one week after Bobby's arrival in Los Angeles.

Store owners, motel managers, and gas station attendants recognized early on that even the poorest travelers required food, automobile maintenance, and adequate lodging. Just as New Deal work relief programs provided employment with the construction and the maintenance of Route 66, the appearance of countless tourist courts, garages, and diners promised sustained economic growth after the road's completion. If military use of the highway during wartime ensured the early success of roadside businesses, the demands of the new tourism industry in the postwar decades gave rise to modern facilities that guaranteed long-term prosperity.

In 1953, the first major bypassing of US 66 occurred in Oklahoma with the opening of the Turner Turnpike between Tulsa and Oklahoma City. The new 88-mile toll road paralleled US 66 for its entire length and bypassed each of the towns along 66. The Turner Turnpike was joined in 1957 by the new Will Rogers Turnpike, which connected Tulsa with the Oklahoma-Missouri border west of Joplin, MO, again paralleling US 66 and bypassing the towns in northeastern Oklahoma in addition to the entire state of Kansas. Both Oklahoma turnpikes were soon designated as Interstate 44, along with the US 66 bypass at Tulsa that connected the city with both turnpikes.

The Chain of Rocks Bridge by-passed Route 66 around the city of St. Louis

Originally, highway officials planned for the last section of US 66 to be bypassed by interstates in Texas, but as was the case in many places, lawsuits held up construction of the new interstates. The US Highway 66 Association had become a voice for the businesses which feared the loss of their businesses. Since the interstates only provided access via ramps at intersections, travelers could not pull directly off a highway into a business. At first, plans were laid out to allow (mainly national chains) to be placed in interstate medians. Such lawsuits effectively prevented this on all but toll roads.

Some towns in Missouri threatened to sue the state if the US 66 designation was removed from the road, though lawsuits never materialized. Several businesses were well known to be on US 66, and fear of losing the number resulted in the state of Missouri officially requesting the designation "Interstate 66" for the St. Louis to Oklahoma City section of the route, but it was denied. In 1984, Arizona also saw its final stretch of highway decommissioned with the completion of Interstate 40 through Williams. Finally, with de-certification of the highway by the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials the following year, US Highway 66 officially ceased to exist.

Roadside Architecture

The evolution of tourist-targeted facilities is well represented in the roadside architecture along U. S. Highway 66. For example, most Americans who drove the route did not stay in hotels. They preferred the accommodations that emerged from automobile travel - motels. Motels evolved from earlier features of the American roadside such as the auto camp and the tourist home. The auto camp developed as townspeople along Route 66 roped off spaces in which travelers could camp for the night. Camp supervisors - some of whom were employed by the various states - provided water, fuel wood, privies or flush toilets, showers, and laundry facilities free of charge.

The national outgrowth of the auto camp and tourist home was the cabin camp (sometimes called cottages) that offered minimal comfort at affordable prices. Many of these cottages are still in operation. Eventually, auto camps and cabin camps gave way to motor courts in which all of the rooms were under a single roof. Motor courts offered additional amenities, such as adjoining restaurants, souvenir shops, and swimming pools. Among the more famous still associated with Route 66 are the El Vado and Zia Motor Lodge in Albuquerque, New Mexico.

In the early years of Route 66, service station prototypes were developed regionally through experimentation, and then were adopted universally across the country. Buildings were distinctive as gas stations, yet clearly associated with a particular petroleum company. Most evolved from the simplest "filling station" concept - a house with one or two service pumps in front - and then became more elaborate, with service bays and tire outlets. Among the most outstanding examples of the evolution of gas stations along Route 66 are Soulsby's Shell station in Mount Olive, Illinois; Bob Audettes' gas station complex in Barton, New Mexico; and the Tower Fina Station in Shamrock, Texas.

Route 66 and many points of interest along the way were familiar landmarks by the time a new generation of postwar motorists hit the road in the 1960's. It was during this period that the television series, "Route 66", starring Martin Milner and George Maharis drove into the living rooms of America every Friday. By today's standards, the show is rather unbelievable but in the 1960's, it brought Americans back to the route looking for new adventure.

Excessive truck use during World War II and the comeback of the automobile industry immediately following the war brought great pressure to bear on America's highways. The national highway system had deteriorated to an appalling condition. Virtually all roads were functionally obsolete and dangerous because of narrow pavements and antiquated structural features that reduced carrying capacity.

Ironically, the public lobby for rapid mobility and improved highways that gained Route 66 its enormous popularity in earlier decades also signaled its demise beginning in the mid-1950's. Mass federal sponsorship for an interstate system of divided highways markedly increased with Dwight D. Eisenhower's second term in the 'White House. General Eisenhower had returned from Germany very impressed by the strategic value of Hitler's Autobahn. "During World War II," he recalled later, "I saw the superlative system of German national highways crossing that country and offering the possibility, often lacking in the United States, to drive with speed and safety at the same time."

The congressional response to the president's commitment was the passage of the Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956, which provided a comprehensive financial umbrella to uderwrite the cost of the national interstate and defense highway system. By 1970, nearly all segments of original Route 66 were bypassed by a modern four-lane highway.

In many respects, the physical remains of Route 66 mirror the evolution of highway development in the United States from a rudimentary hodge-podge of state and country roads to a federally subsidized complex of uniform, well-designed interstate expressways. Various alignments of the legendary road, many of which are still detectable, illustrate the evolution of road engineering from coexistence with the surrounding landscape to domination of it.

Route 66 symbolized the renewed spirit of optimism that pervaded the country after economic catastrophe and global war. Often called, "The Main Street of America", it linked a remote and under-populated region with two vital 20th century cities - Chicago and Los Angeles.

The outdated, poorly maintained vestiges of U.S. Highway 66 completely succumbed to the interstate system in October 1984 when the final section of the original road was bypassed by Interstate 40 at Williams, Arizona.

Now that the highway has celebrated its 75th birthday, its contribution to the nation must be evaluated in the broader context of American social and cultural history. The appearance of U.S. Highway 66 on the American scene coincided with unparalleled economic strife and global instability, yet it hastened the most comprehensive westward movement and economic growth in United States history. Like the early, long-gone trails of the nineteenth century, Route 66 helped to spirit a second and perhaps more permanent mass relocation of Americans. We only hope it does not meet the fate of these once-famous arteries.

Route 66 based American Solar Challege route 2003

Route 66 Facts and Trivia

Take a detour down memory lane on Route 66. It's been immortalized in films, songs, books, and - now - in GPS Maps. There are several great segments of the original route John Steinbeck called "the Mother Road," and in-between there's always the interstate. The path to adventure traveled by Tod and Buz in their red Corvette on the namesake 1960's TV series still exists - you just might need a little help finding it with your GPS.

National

Historic Route 66 Federation Email click here

Associations

National Historic Route 66 Federation The California Route 66 Preservation Foundation New Mexico Route 66 Association The

Illinois Route 66 Association The

Norwegian Route 66 Association Mojave

Desert Heritage and Cultural Association The

Lebanon/Laclede County Route 66 Society

Preservation Partners

The National Route 66 Corridor Preservation Program administered by the National Park Service

Museums

California Route 66 Museum - Victorville, CA National Route 66 Museum - Elk City, OK Mother Road Museum - Barstow, CA Oklahoma

Route 66 Museum The Illinois Route 66 Museum and Hall of Fame

Attractions

Arcadia

Old Round Barn Roy's

Cafe The

Afton Station Henry's

Rabbit Ranch

General Interest

Arizona

Route 66 History Route

66 Weather and Route 66 Cities With Websites Michael

Wallis USA

Tour: Route

66: Empires of Amusement Primarily

Petroliana Resolute Roadside

Peek PAC

Tour ExitHere.net Marian

Clark The

Arizona Reporter PostMarkArt Route

66 Photography - Shellee Graham The

Mother Road Rally Skip

Curtis Tour

Route 66 through the California desert Gallery66.us The

famous Santa Fe Harvey Houses Scenic

St. James, Missouri - a Route 66 classic. John

& Lenore Weiss: - The noted Route 66 authors offer bus tours and

group presentations. Artist,

Author, James Kingneon Cucwua. Parsa's

Virtual Route 66 Roadtrip Windy

City Road Warrior.com - Discover Chicago's Route 66

Photos/Postcards

A

Trip Down The Mother Road. Satellite

images of Route 66. Lost

America

Hotels/Motels

Motels

of the Southwest La

Hacienda Grande Blue

Swallow Motel The

Route 66 Inn Fender's

River Road Resort

Restaurants/Nightclubs

Ariston

Cafe Litchfield, IL The

Midpoint Cafe & Gift Shop The historic Fair Oaks Pharmacy in S. Pasadena The

famous Rock Cafe in Stroud, OK

Rental Cars/Motorcycles

Sedona

Rent-A-Hog Eaglerider Harley Davidson Rentals Cruise

America Route

66 Riders Harley Davidson Rentals - Auto

Driveaway Co.

Retail Stores/Gift Shops

The

Savvy Traveller National

Historic Route 66 Federation Angel's

Barbershop Things

Antiques and Collectibles

Former U.S. Highway 66 is also known as "The Mother Road", "The Main Street of America" and "The Will Rogers Highway".

|

|

EDUCATION | SOLAR CAR RACING TEAMS | SOLAR CAR RACING EVENTS | FILMS | MUSIC |

|

The

content of this website is copyright © and design copyright 1991 and 2006

Electrick Publications. All rights reserved. The bluebird logo |

US

ROUTE 66

US

ROUTE 66