|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

COLIN CHAPMAN

When the name Lotus is mentioned the man, Colin Chapman comes immediately into mind. The founder of Lotus, Anthony Colin Bruce Chapman, was born of ordinary, parents in the London area of England on May 9, 1928. His father was a hotel manager. His youth was filled with typical English boyhood antics and schooling. By the age of 17 he was entering the University College of London University to study engineering. And, as any story about motorcars would begin, Colin was already travelling about on his Panther 350cc motorcycle. Unfortunately the Panther was short lived and by the University's welcoming dance the Panther was written off, having been smashed into the door of a taxi. His interest motorcars had yet to be piqued but, with the arrival of Christmas Colin was presented with a '37 maroon Morris 8 Tourer.

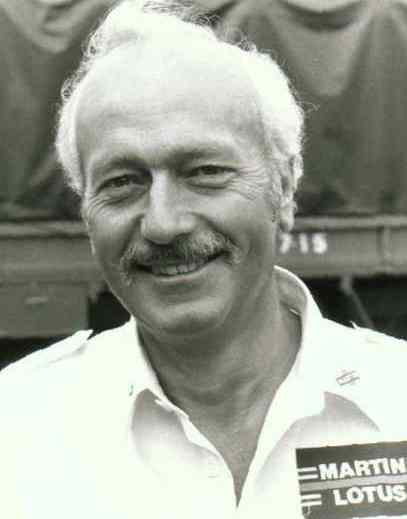

Colin Chapman

The Morris was lavished with Colin's attention and was used for transporting himself to and from is home and the University. Often he would have fellow students Colin Dare and Hazel Williams, who Colin had met at a dance in 1945, as passengers in his journeys. These journeys were not without peril and adventure. But Colin had turned them into sport, always interested in setting new records for traveling the distance between home and Hazel's, Colin Dare's and school in the shortest amount of time.

It was soon after entering the London University, that he and Colin Dare began a second hand car sales business. The year being 1946 cars were scarce and the business boomed, growing to one to two cars being bought and sold per week. Often lectures were skipped in order that "deals" could be secured. As the inventory of cars grew the space to keep the cars became insufficient and the two Colins were seen stashing cars in the lock up shed behind Hazel's home. The normal buying and selling became easy and the two Colins grew into modifying and improving their cars before placing them on the block. This brought greater profits, but more work. This booming business was not to last as in 1947 the British government did away with the basic petro rationing and new cars became plentiful and the demand for second hand vehicles crashed. The business was disbanded and what remained was an old clapped out 1937 Austin 7.

He qualified as a pilot while still a student, then graduated as a civil engineer from University College London in 1948, before spending his National Service as a pilot in the RAF.

In 1952 he founded the Lotus Engineering Co Ltd, using a small loan from Hazel Williams, his future wife, to buy and sell used cars. Initially he modified and raced these cars himself in trials and hillclimbs, selling each to finance building or converting the next, while working full-time for the British Aluminium Company. In 1954 Chapman was able to take up running Lotus Engineering as a full-time job, and to set up Team Lotus to oversee the racing. By this stage he was already working as a consultant for the BRM and Vanwall Formula 1 teams. Among his first paid employees were Graham Hill, and Keith Duckworth and Mike Costin (the pair who founded Cosworth - the latter became Lotus's chief aerodynamicist, having previously worked for de Havilland).

Austin Seven

Lotus's Formula 1 debut came in 1958. Over the next 24 years, Chapman's moustache and cloth cap (which he threw into the air whenever Team Lotus won a race) would become familiar at tracksides around the world. He was a constant source of technical innovation, and it is probably fair to say that he did more than anyone else to change motor racing worldwide. He died of a heart attack on 16 December, 1982. By this time, he was embroiled in the murky financial waters of the Delorean scandal, that would eventually also claim the life of his team.

Chapman had a legendary ability to throw himself into a new field of study. He is said to have learnt accounting in a single weekend when it became necessary for the running of his company. He showed the same ability in several other fields, such as aerodynamics, where he read every book he could find on the subject. If he had a weakness, it was that he was never satisfied with simply patiently developing something. In classic alpha-personality style, he would quickly become bored and start looking for the next breakthrough. The other classic personality trait that he displayed was introversion. Although often regarded as not being a 'people person' and as hard to approach, Chapman had several close friends in whose company he obviously delighted. This second weakness would nearly lead him to disband the Lotus team after Jim Clark was killed - but it was the former that would, years after Chapman's own death, eventually have effects that helped to bring the team down.

CHAPMAN AS DRIVER

Chapman started out building cars to drive himself. He developed quite a reputation around the British club-racing scene, especially in 1951 as he dominated in the Lotus III so completely that the formula was changed to outlaw his car. He entered the 1956 French Grand Prix, qualifying 5th in a Vanwall, though he did not start the race. His race career was curtailed by his growing responsibilities to the team - he was no longer an asset that could be risked in the increasingly lethal world of top-level motor racing of the early 1960s. His only other major race was the 1960 British Grand Prix touring car support race, which he won in a Jaguar.

GENIUS

A true genius, many of his ideas can still be seen in Formula 1 and other top levels of motor sport (such as Indycars) today.

He pioneered the use of struts as a rear suspension device. Even today, struts used in the rear of a vehicle are known as Chapman struts.

His next major innovation was to adopt the use of monocoque (stressed-skin) unibodies (i.e. it replaced both the body and frame, which until then had been separate components) for cars. This was the first major advance in which he introduced aeroplane technology to cars. The resultant body was both lighter, stronger (i.e. stiffer), and also provided better driver protection in the event of a crash. The first Lotus to feature this technology was the Lotus Elite, in 1958. Amazingly, the body of the car was made out of fibreglass, making it also the first car made out of composites.

In 1962 he extended this innovation to racing cars, with the revolutionary Lotus 25 Formula 1 car. This technique fairly quickly replaced what had been for many decades the standard in racing-cars, the tube-frame chassis. Although the material has changed from sheet aluminium to carbon fibre, this remains today the standard technique for building top-level racing cars. It was he who really brought aerodynamics into being a first-rank influence on car engineering. He popularized the concept of positive aerodynamic downforce, through the addition of front and rear wings. Early efforts were mounted 3 feet or so above the car, in order to operate in 'clean air' (i.e. air that would not otherwise be disturbed by the passage of the car). However the thin supporting struts failed regularly, forcing the FIA to require the wings to be attached directly to the bodywork. He also pioneered the movement of radiators away from the front of the car, to decrease air resistance at speed. Both of these concepts also remain features of high performance racing cars today.

Another concept of Chapman's was "ground effect", whereby a partial vacuum was created under the car by use of venturis, generating "downforce" which held it securely to the road whilst cornering, etc. (Modern racing cars generate enough downforce that they could theoretically be driven on the ceiling once they are up to speed, although the fuel system and other parts of the car rely on gravity and so a Formula One car could not in reality be driven upside down.) Initially this technique utilized sliding "skirts" which made contact with the ground to keep the area of low pressure isolated. The skirts were also banned, for if during cornering the car went over a curb, and the skirt were damaged, downforce was lost, and the car could became extremely unstable. Downforce remains a critical part of racing car technology, and modern designers, aided by extensive wind tunnel testing, have regained most of what was lost through the banning of skirts.

His last major technical innovation was the creation of the dual-chassis car design, in which different parts of the vehicle were given different suspension. The banning of this by the FIA really upset him, and may have precipitated ill health, which was to dog him for the final few years of his life. However, it inspired active suspension, pioneered by Lotus.

It wasn't purely as a designer that he excelled; he was also a canny businessman who introduced sponsorship into Formula 1, beginning the process of raising the sport from gentlemens' entertainment to a multi-million pound enterprise. Unfortunately, he made a bad decision to become involved with a new venture of his friend John De Lorean, to manufacture sports cars. The full extent of his involvement has never been made public, but it is believed he would have been prosecuted for his involvement of inveigling government funds.

Colin Chapman

1950s Origins

The first car that we now call a Lotus was built by Colin Chapman in a lock-up garage behind his girl friend's house in 1946 or 1947. At the time he called it an Austin Seven Special, and it competed in mud plugging trials in 1948. The first car he actually called a Lotus, at the time, was built in 1949 whilst he was in the Royal Air Force, and was built in the same lock-up garage. It was also intended for competition in trials, and was fitted with a more powerful Ford engine instead of the Austin Seven unit used in the previous car. Chapman made sure that it could also be used as a practical road car, and in 1950 entered it in his first race at Silverstone, where he took on a Type 37 Bugatti and won! This changed his whole interest in motor sport, and he decided to build a road racing sports car to compete in the new 750 Formula in 1951.

This car was called the Lotus Mk III, and his previous car became the Lotus Mk II, and the original Austin Seven Special became the Lotus Mk I - long after it had been sold! The new racer was started in the same lock-up garage, but then Chapman met the Allen brothers, Michael and Nigel, who had a very well equipped workshop beside their house, and were persuaded to join him in building a team of three racers for the new Formula. They only had time to finish one, and it was an enormous success in 1951, winning every race it finished in the 750 Formula, and often beating cars of double the engine size in other races.

The Lotus Engineering Company was formed on 1st January 1952 with Michael and Colin as the two directors, and they started to build the car which was to be the first production Lotus, the Mark VI. In 1952, fitted with the new 1.5 litre Ford Consul engine, it raced twice before being written off in a road accident. Several orders had ben received from customers, and an order for six chassis frames was placed by Lotus with two friends who formed the Progress Chassis Company to build them. Lotus Engineering Company became a limited liability company on 25th September 1952., on 1st January 1953 Chapman was joined by Mike Costin, both working in their spare time from their day jobs.

Racing success with the Mark VI in 1953 encouraged Chapman to build a streamlined version for 1954, and fitted with a 1.5 litre MG engine, this car, and the earlier Mk VI, beat the works Porsche in the sports car race before the British Grand Prix at Silverstone. Lotus had arrived, and new cars were being ordered in sufficient numbers for Chapman and Mike Costin to give up their day jobs and work for Lotus full time on 1st January 1955.

Lotus first raced at Le Mans in 1955 with the Mk IX. Chapman and Flockhart lost some time due to a slipping clutch but were running well when the car was disqualified when Chapman reversed it out of a sand bank after an off-road excursion.

The Eleven sports cars followed, and with the new Coventry Climax engine they were the cars to have if you wanted to win races. In 1957 an updated version of the Mark VI appeared called the Seven. This was so successful that it is still in production now (called the Caterham Seven).

A single seat Lotus appeared in 1957 and Lotus won the Index of Performance at Le Mans. Lotus had outgrown the tiny premises at Hornsey, and in 1959 moved to a purpose built factory at Cheshunt.

Lotus Elite 1960

1960s Growth

The new factory was needed to assemble the revolutionary new Lotus Elite, a two seater coupe with integral glassfibre body/chassis. Lotus entered Formula 1 in 1958 and by 1960 with their first rear-engined car, the Eighteen, a Lotus won its first Grand Prix, driven by Stirling Moss.

The 1960s showed steady growth of Lotus both on the race track, where Jim Clark won two World Championships, and in the market place with the new Lotus Elan, still thought by many to be the best ever sports car, and in collaboration with Ford, the Lotus-Cortina. The new DFV engine from Cosworth brought further F1 success, and Lotus won at Indianapolis.

The rear engined Europa followed, and Chapman, keen to be rid of his kit-car image, sold off the Seven to Caterham Cars and prepared to start building cars for a higher income bracket. Cheshunt was too small, and the final move was made to Hethel, near Norwich in Norfolk in 1966 where a new four seater car, also named the Elite, entered production with their own 2 litre Lotus engine.

1970s Expansion

On the track the 70s were a continuing success story in all the single seat formulae, but sports car racing had virtually ceased with the unsuccessful Lotus 30 and 40 The Elite was followed by the lower priced Eclat, the Esprit two seat Coupe, and the Sunbeam Lotus which won the Rally Championship in 1981. Then in 1982 came the shattering news that Colin Chapman had died at the age of only 54. To many of those interested in historic Lotus cars that was the end of the era, and Team Lotus withdrew from Formula 1 in 1995. Group Lotus continues to be a leading figure in the world of automotive engineering, and recent success with the Elise has done much to restore their deserved prestige.

The Glory Years in F1

In 1965 the team won both F1 championships, the Indy 500, the Australian Tasman series and the British and French F2 titles. In fact, Jim Clark led every lap of every race that he finished that year and scored maximum points. Just five years after their first F1 victory, Lotus were indisputably the best team in the world. They would win the Tasman series again in 1967 and 1968.

Their 1966 season was hampered by uncompetitive BRM engines, having switched from Coventry Climax that year. But the following year bought a return to form with a new chassis design and a new engine supplier. The Lotus 49 was another seminal car. It won first time out in 1967, though reliability issues prevented it from taking the title that year. It took the idea of stressed panels a step further, using the engine as stressed member (in other words, the wheels and rear wing were connected directly to the engine. There was no rear bodywork). Doing away with the rear bodywork saved on weight, and the air was so turbulent by the time it had passed over the whole car that the diffuser - rear aerodynamics - was having little effect anyway. As a side-effect, this also gave the best possible view of the Ford DFV engine, which would go on to win more races than any other power-plant. The Ford was the first engine to be custom-built by the manufacturer for the team. Again, all top-level motorsport engines are now built this way. Wings and slick tyres appeared around this time but were not developed by any F1 team. They were virtually the only significant technical advances of this period not made by Lotus.

Like the 25, the 49 was known as much for its sleek good looks as for its performance on the track (though those looks were marred in later seasons by the addition of unsightly wings). To cap a superlative car, the Jim Clark/Graham Hill driver line-up was one of the strongest ever.

The Ford-Cosworth engine proved so powerful that the F1 authorities asked Chapman to make it available to other teams from 1968 onwards, as otherwise there would be no serious competition. For nearly 20 years afterwards, aside from Ferrari and BRM, all race-winning teams used off-the-shelf Ford Cosworth engines. Only the arrival of the turbo era eventually displaced it.

Jim Clark and Driver Deaths

Scottish ex-farmer Jim Clark was an indispensable part of the Lotus team during this period. He was possibly the most naturally talented racing driver ever. He won two F1 titles before dying in an F2 race in 1968. Lotus was the only team he ever drove for, and he was one of Chapman's closest friends; the two quiet personalities seemed to match. Despite his prowess, Clark never won at Monaco, regarded by many as the circuit that tests a driver's skill the most. In part this is because, as mentioned above, he missed the Monaco Grand Prix several times to compete in the Indy 500. Chapman was devastated by Clark's death, and considered closing the team. Only Graham Hill's strong leadership and championship-winning form held the team together.

Jochen Rindt also died at the wheel of a Lotus (uniquely, he became champion posthumously in 1970), as did Alan Stacey. These events - and Sterling Moss' near-fatal crash in one of Chapman's cars - affected Chapman profoundly, though probably never to the same extent as Clark's death. Long after Moss was able to laugh off his injuries, Chapman could be moved to anger by any light-hearted reference to the incident.

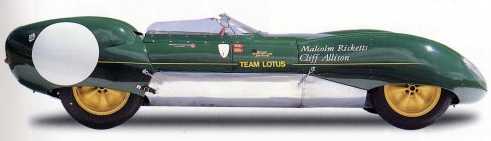

Team Colours and Sponsorship

When Lotus first entered Formula 1, every car ran in its national colours. For British cars like Lotus, that meant British Racing Green. The teams differentiated themselves by using different shades, or by using coloured stripes. The Lotus team colours were therefore green with a yellow stripe down the centre of the car.

Sponsorship at this time was limited to a few oil and tyre companies paying the teams to be able to say that their products were used. When the rules were relaxed, Chapman was the first to repaint his entire car in his sponsor's colours - the Gold Leaf tobacco brand. This was to be the start of a long association between F1 and tobacco money, and all race teams now run in sponsors' colours.

In the late seventies, Lotus switched brands to John Player Special. Their black-and-gold livery became one of the most famous in sports sponsorship history. Chapman also became the first team-owner to name his cars after his sponsor, insisting that they be known as John Player Special Lotuses. Again, this practice has become standard throughout all formulae of motor-racing.

LOTUS ROAD CARS

Despite not being the race team, Lotus Cars occasionally entered cars in sports events. Here too, Lotus ingenuity was in evidence. The road cars were the first to use pop-up headlamps for aerodynamic efficiency. The Chapman strut (essentially a McPherson strut used on the rear suspension) is now a standard suspension design, though it has disadvantages in terms of height and side-load. The famed 'backbone' layout (a central monocoque with the bodywork radiating from it) remains one of the most efficient chassis designs, giving superb handling. Following is a list of some of the best-remembered Lotus road-cars.

Lotus 7

Lotus Esprit Turbo

Lotus Elan

In 1986, Lotus was taken over by General Motors following the Lotus group's disastrous collapse. In 1990 they won the US SECA sports-cars championship, with victories in half the races. They also produced an upgraded version of the Vauxhall Carlton (known as the Omega in the USA). In 1992, Chris Boardman won Olympic gold on a carbon-fibre, asymmetric Lotus bicycle, demonstrating that not only was the company still capable of innovative design, it was not restricted to motor-vehicles. 1992 also saw another US sportscar championship title. Yet the company continued to lose money, and in 1993 it was sold to Bugatti. Three years later, it was sold again, to Proton. This is now the only surviving arm of the company, and appears to be running smoothly. It has recently moved back into the consultancy arena, tweaking the suspension of a few Protons and designing the Vauxhall VX220.

Lotus Elsie chassis

Lotus Engineering - Pure Lotus

The consultancy business was always the backbone of the Lotus group. When times were hard for the road car division, the engineering division could be relied upon to provide a steady income. It is therefore perhaps ironic that it was this division that was eventually to lead to the group's collapse through its involvement with the Delorean scandal. Much of the 54 million pounds paid out to the Delorean Motor Company to build a plant in Belfast disappeared. Lotus were involved because they were approached by Delorean to put the finishing touches to the troublesome chassis design (they scrapped it and used an Esprit chassis, a fact which was kept quiet at the time). It seems that Chapman's need to be constantly finding a new way around the rules rather than patiently improving an existing design extended to his financial dealings also, and it is probable that his demise saved him from a lengthy and ignominious prison term. When the scandal broke and Lotus' involvement became clear, including a criminal investigation into its Managing Director and other senior personnel, sponsors for the company dried up. With no recent racing successes to fall back on, the race team foundered, taking the other branches of the business with it.

As detailed above, the road-car business survives, and the rights to the F1 team name occasionally pass hands for small sums of money. But the Lotus name is already carved deeply into the fabric of automotive design, and will remain there.

Lotus is working at top speed to design and develop a secret new £75,000 supercar to replace the 25-year-old Esprit in two years' time. Depicted below is an official Lotus drawing and, above, enhanced by computer design, the new Esprit – a mid-engine two-door coupé with compact styling and dimensions, sophisticated aerodynamics, ultra-agile handling and a top speed close to 200mph – is being engineered to suit all the major car markets of the world. Lotus aims to offer markedly better performance and value for money than established opponents like the Porsche 911, Ferrari 360 and Lamborghini Gallardo.

Lotus Design supplied this illustration of a new supercar in 1995, which may or may not be the new Esprit.

IN MEMORIAM

Kennen

Sie ABS, ESP, PDC, HDC, SBC, ABC oder Servolenkung und elektrische

Fenster-heber?

The late Colin Chapman

Lotus 7 parts kit

Lotus Club Officers & Contacts

Are shown below. To contact them by e-mail click on the person's name. Chairman Ean Pugh

Vice Chairman Mike Marsden

General Secretary John Oakley

Membership Secretary and Treasurer Peter

Ross

Editor Mike Wilson

Competition Secretary Kevin

Whittle

Links :

The Website is sponsored by Solar Cola

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The

content of this website is copyright © and design copyright 1991 and

2006 Electrick Publications and NJK. All rights reserved. The bird |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

COLIN CHAPMAN and LOTUS

COLIN CHAPMAN and LOTUS